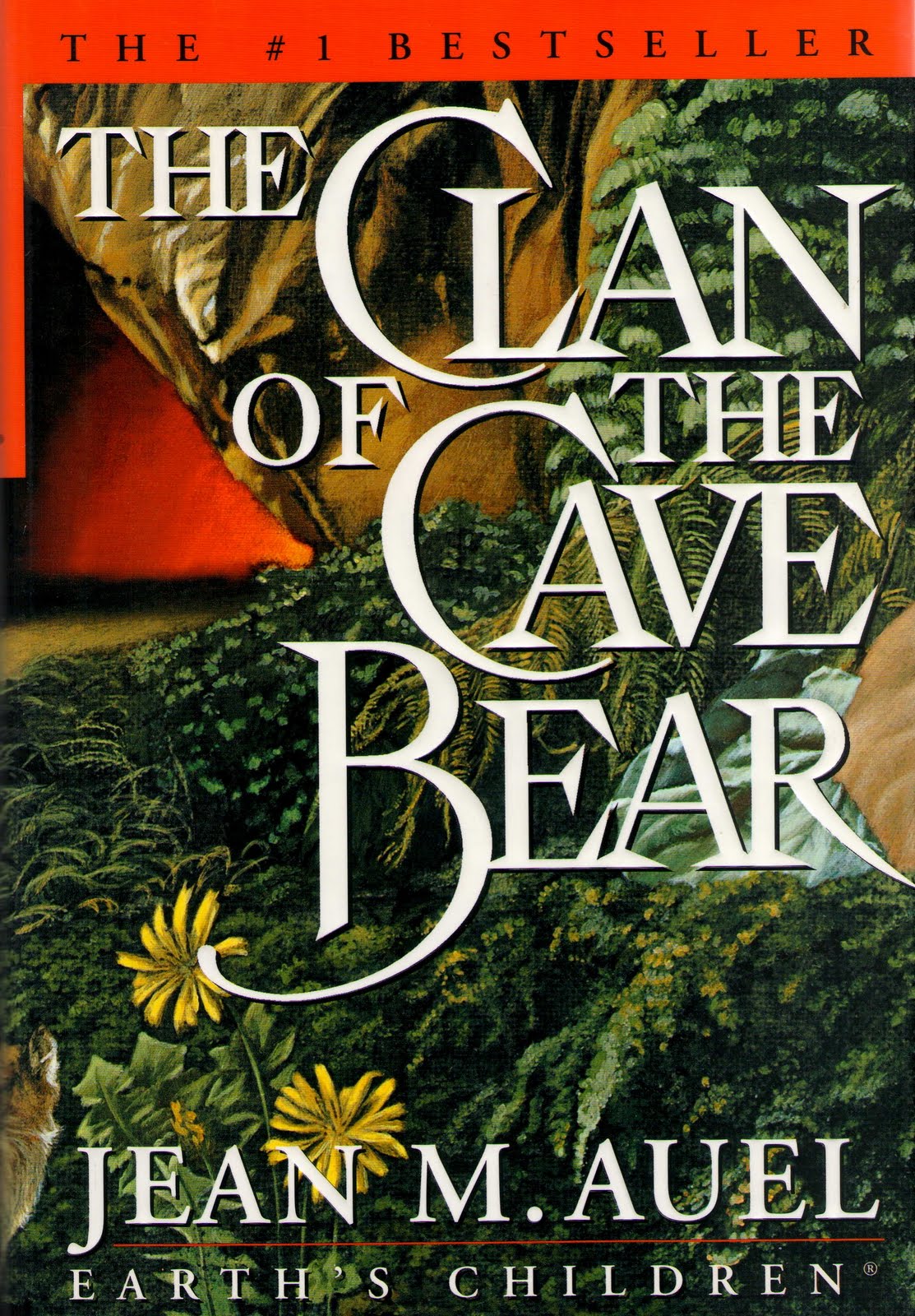

These were lions, hyenas and people that were quite comfortable living anywhere convenient cave deposits sometime preserved their bones and may have provided shelter or dens now and then but there was no obligate connection. But there’s a lot of other interesting stuff.įor one thing, “cave” as applied to most Pleistocene mammals – “cave” lion, “cave” hyena, “cave” man – is a misnomer. As it turns out, the supposed “tombs” in the Drachenloch were natural rock formations and there’s no evidence for ritual interaction between Pleistocene humans and Pleistocene cave bears (well, almost none). By the 1980s, the idea was sufficiently ingrained to make it into novels and films (which were praised for their archaeological accuracy).Īlas, to paraphrase the Red Queen, science moves so quickly you have to run as fast as you can just to keep up with it, and at about the same time that the cave-bear clan was turning up on the best seller lists and in the movies Finnish paleontologist Björn Kurtén had given in to the fate set by his name (“Björn” is Swedish for “Bear”) and wrote The Cave Bear Story, based on a lifetime of research on the titular animal.

After a while some unknown science populizers must have picked up on it perhaps there were some new stories about prehistoric cults slaughtering and dismembering of giant cave bears and the carefully placing their bones in stone “tombs” in caves.

Gallischen naturwissenschaftlichen, probably not available on most newsstands. Thus when Swiss paleontologist Emil Bächler excavated the Drachenloch Cave between 19, his initial reports of ritual use of bear bones appeared in the Bericht der St. An illustration of the way scientific information gradually infuses popular culture: there are technical papers about some discovery, followed some years later by more popular accounts, followed some years after that by appearance in literature.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)